How Big is Your Sensor and Does it Really Matter?

The conversation, [some might say, argument] about camera sensor sizes has been raging since the advent of digital photography. In his first feature for PhotoBite, Ant Macina deliberates the misconceptions about camera sensor size and poses the question, ‘does size really matter’?

It’s a question that’s been asked time and again; ‘do I need to be shooting large format’? OK, it may be a noise that’s slightly louder coming from the micro four-thirds camp who, let’s be honest, feel the need to justify their choices slightly more than the full-frame brigade, and most shooting with APS-C sensors would likely not know the difference or may not care.

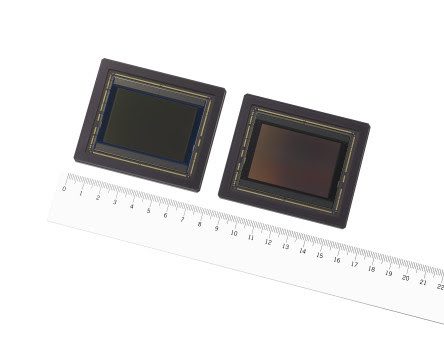

Starting at the front, then, there are four main sensor sizes as far as interchangeable lens cameras [ILCs] tend to go. They are, starting with the smallest, Micro Four Thirds [M4/3], then we have APS-C, [crop sensor] full-frame and digital medium format.

Among these four sizes, full-frame is broadly seen as the default for enthusiast and professional photographic work, with medium format being an expensive niche and crop sensors such as APS-C seen as entry-level or hobbyist option with M4/3 hanging around all of the above. Plenty of great, award-winning work is shot with smaller sensor sizes, and plenty of studio photographers using high-end brands such as Hasselblad and Phase One cameras would scoff at anything smaller than medium format for their ‘crucial’ work. So, what impact does sensor size have and does it matter to pro and consumer image-makers?

Why Full-Frame?

36mmx24mm, is considered the ‘standard’ digital sensor size. It’s essentially the same as the dominant film format of the 20th century, i.e. 35mm film. This common film stock transformed photography, from Henri Cartier-Bresson and his famous Leica camera to the classic SLRs from Nikon, Canon, Minolta and Olympus that shot the latter half of the century. It became a standardising force in photography where your choice of film was as important as the body and lens you put in front of it. Many of these classic lens libraries gave us the look we know, with focal lengths that were commonly produced becoming defining choices for lens options, such as 24mm, 35mm, 50mm and 85mm.

The Rebirth of Crop Sensor Formats

The rise of digital photography came with an enormous extra cost. Digital imaging sensors were, and still are, a significant part of the cost of a camera body. In the early days, it was prohibitively expensive to put a full-frame sensor in a camera as that instantly meant the price had to balloon into multiple thousands. If you could have told early digital photographers that there would, in time, be brand-new full-frame cameras for around £1,000, they would scarcely have believed you. That gave rise to the birth of crop-sensor digital SLRs, lead by the Canon ‘Rebel’ line that would give budding photographers a good platform to start from. They tended to share a mount system with their more expensive, full-frame, professional stablemates, yet they were often furnished with revolutionary features first and enjoyed some trickle-down of high-end technology as economies of scale and recouping R&D investment with expensive professional bodies meant cost would lower over time.

There was, however, a drawback to the APS-C DSLR, [who says photography is too fond of acronyms?] and that was in the lens selection. As they shared a mount with their full-frame cousins, the APS-C bodies also relied on them for lenses, with only a handful of dedicated primes and a smattering of variable-aperture consumer-grade zooms. This opened up a niche market for third-party specialised APS-C lens manufacturers and that was quickly filled by the likes of Tokina, Tamron and especially Sigma. Using a full-frame lens on an APS-C body is perfectly fine for most cases, but it does mean that you’ll have to deal with the crop factor.

The ’E’ Word

I could write an entire thesis on the merits of ‘equivalency’ but suffice it to say that at its simplest, the crop factor will tell you what the image from a smaller or larger sensor will look like in full-frame terms. You’ll often see it employed with regards to focal length saying the lens is ‘equivalent to Xmm’ but to give you the right idea of how it will look, it’s important to multiply the aperture by the crop factor as well to indicate the depth of field of the image. For example, to get the same field of view across all the major sensor sizes, we’d need to apply their crop factor to the aperture as well as the focal length. A 20mm f/2 M4/3 lens, a 30mm f/3 APS-C lens, a 40mm f/4 full-frame lens and a 50mm f/5 lens on the smaller medium format options from Hasselblad and Fujifilm would all give the same field of view and depth of field.

In practice, it’s never quite that easy, as lens designs tend to favour fast primes hovering between f/1.2 and f/2.8, with zooms often being considered professional grade at f/2.8 to f/4. This means that with larger sensor sizes it is easier to get a shallow depth of field, as you’ll be using a 50mm instead of a 25mm or 35mm lens on crop sensors, and longer focal lengths will give a shallower depth of field at equivalent apertures.

The Benefits of Smaller Sensors

You might ask yourself why you’d consider a smaller sensor if this is the case? If it’s easier to achieve subject separation with full-frame and it gives a certain professional aesthetic with its larger cameras and bigger lenses. The key is the rise of dedicated crop mounts from Fujifilm, Canon and the M4/3 consortium including Olympus [now OM Systems], Panasonic/LUMIX and Blackmagic Design. These all have much lighter weight when taking into account the total system; even for professionally targeted bodies such as Panasonic’s LUMIX GH line of cameras or Fujifilm’s X-T and X-Pro ranges.

Smaller sensors tend to read faster, cool easier and more quickly and have often had features that rely on processing data at speed much earlier than their larger sensor opposition. Incredible stabilisation from the likes of Olympus and Panasonic has been around for years along with 10-bit video files from Fujifilm and Panasonic, which date back two generations. RAW video at around £1,000 from Blackmagic has been the norm since the first Pocket Cinema Camera; high burst rates for sports and wildlife shooting and options ranging from tiny travel bodies up to large, comfortable professional bodies are all available to suit many needs. It is only quite recently that full-frame bodies have caught up, technologically speaking, so if those features would help you, there are plenty of capable bodies going back years that can be bought at absolute bargain prices.

In essence, crop sensor systems tend to be more feature-rich, cheaper and lighter.

The Benefits of Larger Sensors

Larger sensors offer more mount options, with the big boys, Canon, Sony, Nikon and the historically important yet prohibitively expensive Leica, all involved, along with Panasonic. Fujifilm has skipped full-frame entirely, making the jump to an even larger size; digital medium format.

The sensors used in these cameras all tend to have higher resolution, with M4/3 stuck at circa 20MP at the time of writing and APS-C hovering between 24-32mp depending on your brand of choice. Full-frame offers up circa 60MP of resolution, with the common resolutions of high-end bodies around the 40-50MP mark and medium format offers up to 100MP at the smaller size that Fujifilm cameras sit at, with 150MP, [Phase One camera systems etc] that are a more true medium format.

Beyond that, there is a dynamic range advantage. Theoretically, it should be around a stop of difference between each major size, though in practice it’s considerably less, with sensor age having a larger impact. There will be a separate article delving into that in more detail in future but suffice it to say that the gap isn’t as large as you’d think between the sizes. However, it still exists; as does the advantage of shallower depth of field, allowing cheap full-frame lenses to compete with higher grade crop lenses, aside from zooms where crop mounts have largely caught up unless price is no barrier.

“Whatever you do, enjoy whatever it is you shoot with. After all, it’d not the size that counts – it’s what you do with it!”

The last benefit of full-frame systems is the large market share that Canon, Sony and Nikon each command. On one hand, this means a potentially more secure platform for future investment in lenses and bodies, though I’d argue that for most uses, Fujifilm or M4/3 have already got your needs covered [the less said about Canon’s crop EF-M mount the better]. It also means you don’t have to tolerate full-frame snobs arguing about how you couldn’t possibly get good results with a telephoto lens that isn’t the size and weight of a bazooka, or get a nice portrait without a chunky f/1.2 full-frame prime, ignoring the fact that most professional photography for landscapes, fashion or studio product work is accomplished at smaller apertures.

Conclusions

The key here is to evaluate your needs. You can achieve shallow depth of field with a crop sensor. You can get lightweight kit with a full-frame setup [look to Sigma’s DN lenses for a lovely selection] and you can get the right kit for most needs in any sensor size. Pick what’s right for you, your budget and your needs but remember that glass is more important than any camera body! Take care and enjoy whatever it is you shoot with. After all, it’s not the size that counts – it’s what you do with it!