The Photography of David Lynch: Interview

Fascinated by the ‘murky’ and ‘dark’ nature of David Lynch’s traditional aesthetic in filmmaking, Petra Giloy-Hirtz has produced a collection of his photography entitled ‘David Lynch – The Factory Photographs’.

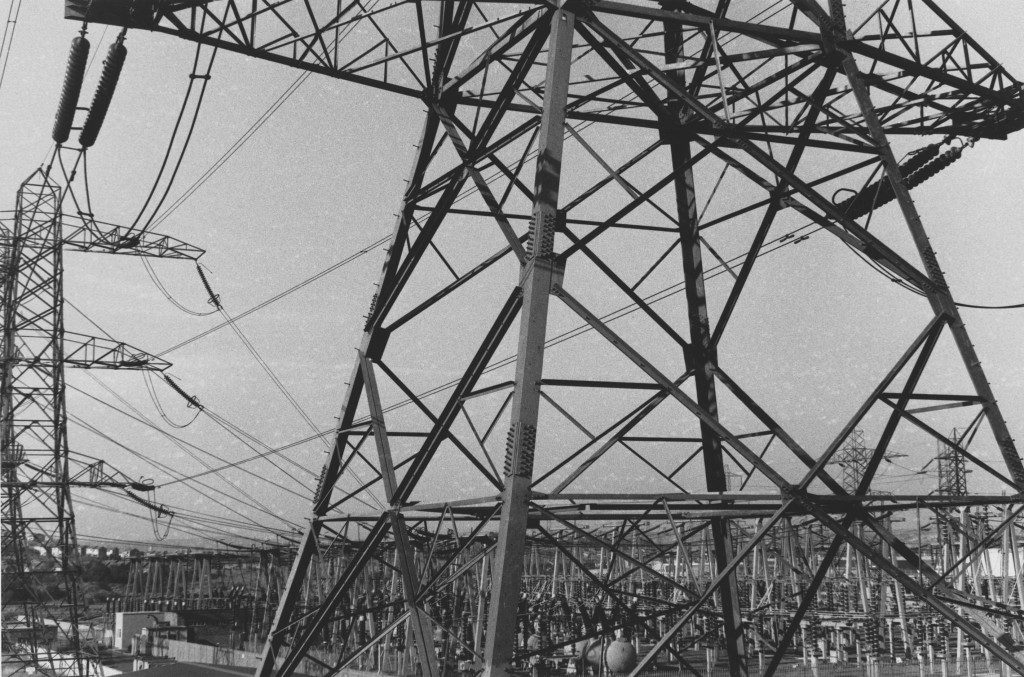

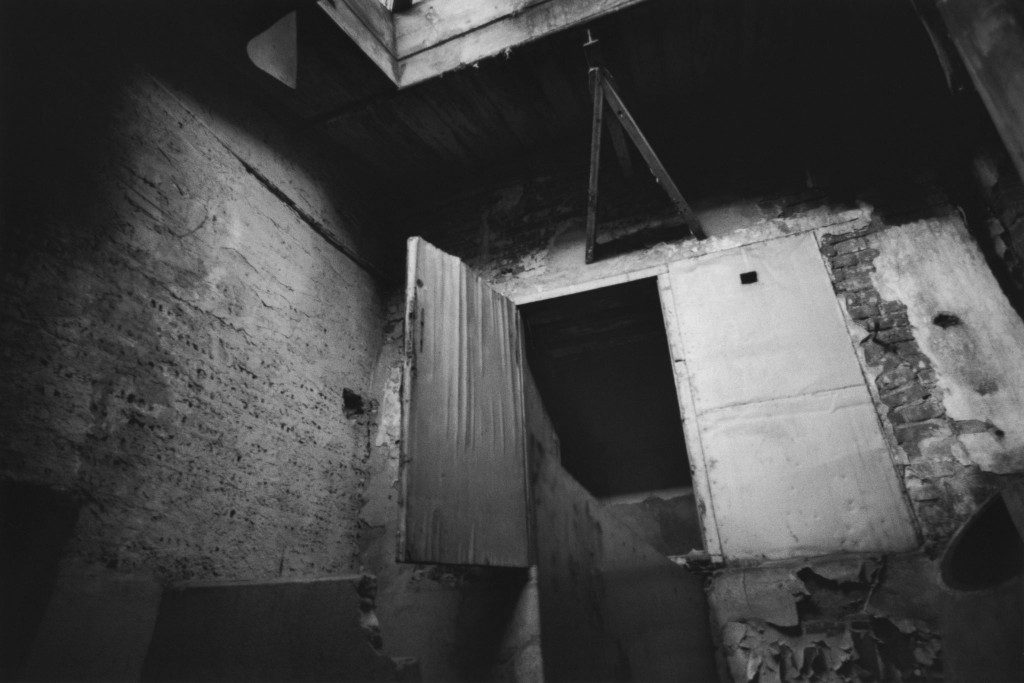

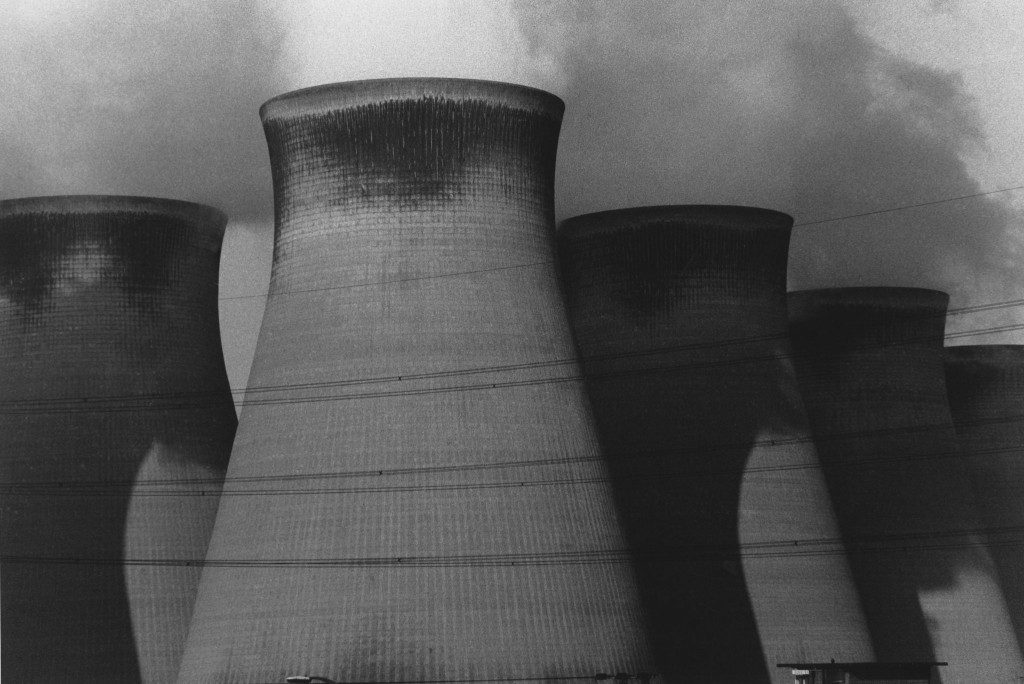

This collection of his photographs, as explained by Petra, reveals his unmistakable signature; surreal imagery resembling dream sequences in its subjects, moods, and shades of colour. The otherworldly spaces, the cypher-like symbols, the strange metamorphoses, the obsession with machines: they certainly remind us of the labyrinthine, enigmatic, and ominous qualities of his films. The buildings are shrouded in fog, vapour, and steam. Raindrops blur the view. It is always autumn or winter and the naked branches of the trees stick out like silhouettes against the grey milky colour of the sky. Brick structures with arches, cornices, domes, and towers, with high windows and portals, resemble cathedrals.

Remnants of a lost world, monuments of a past when factories were proud milestones of progress. And today: flaking paint, collapsing structures, morbid, musty, everywhere devastation and dirt. Realms of shadows, abandoned, uninhabited, no indication of time or place. Deserted wastelands, murky interiors, bizarre details, gutted and quiet.

David Lynch finds beauty in these places. He loves chimneys, smokestacks, and machines, lights, high-voltage electricity, the noise of gears, the smell. He is attracted by these relics of industrialisation and, for more than thirty years now, he has been photographing them, telling stories of destruction, disappearance, and loss.

David Lynch Untitled England late 1980s early 1990s

Petra’s conversation with David Lynch

P: David, thank you for the wonderful privilege of going through all the boxes of your Factory Photographs, a treasure trove of great images. Would you like to tell us something about these photographs?

D: I don’t like to talk about stuff like this Petra, but it is obvious that I like factories. And I love factories that are working factories. But more than that, I love factories that are derelict factories where nature is starting to reclaim the place and you get this fantastic thing of decay with the machines.

It’s so beautiful, what’s going on in these derelict factories. So many of them are so beautiful. They are like cathedrals but mother-nature is reclaiming them. So you catch it in the reclaiming process and this is really thrilling to me.

On the first viewing, one feels them being dark and almost threatening. But that’s only one side. These places of stillness and dignity, have a poetic and even romantic aura, a beauty. Great, great beauty!

P: You refuse to interpret your own work. Do you want the viewer setting up their own story?

D: Sometimes this happens, and what happens, I said this a bunch of times before, is that every viewer gets a little bit of a different thing looking at anything and so it’s a circle between the viewer and the piece. And it’s different with each viewer. It’s really amazing. So you just do the work and watch and see what happens. Some people love it, some people hate it, some people are somewhere in the middle.

P: Do you love to look at these photographs?

D: I love to look at them. It makes me crazy.

David Lynch Untitled Lodz 2000

P: How do you look at them? Do you “hear” them, is there also a sound?

D: Most of these factories are quite quiet. And maybe you hear a wind, because there are so many broken windows, you might hear a wind coming through. But most of these places were shut down. There are some photos from an electrical factory that was still working. And there you hear the happy sound of machinery and generating electricity, lots of smoke and big sounds in a working factory, and that’s a beautiful music. But most of these that we went into, derelict ones, are very quiet, very, very quiet. Just beautiful. They all are uninhabited, no people anywhere. And that is what you feel: time is passing, you feel the presence of death. Obviously you witness monuments of the past, you witness something dying. It’s dead, really. You are witnessing a dead body and watching nature bring it back to the elements. I

It’s already dead. And they will be torn down or turned into something that’s not a factory and it won’t be much anymore. But when you get the opportunity to go into one of these places, it’s like a ticket to heaven.

I am very dedicated to the series of Windows, especially when you catch a view through into nature. I don’t really like the trees and branches unless it’s winter. Then they work with the factories. But a factory in the spring and summer to me is very depressing. I don’t like the greenery going into the factories. I like black and white, winter, black leafless trees. That goes with the factory.

The naked branches as the frames and the broken glass, they are like lines of a drawing. There are shapes and textures in the factory that are so painterly, it’s amazing; absolutely incredible things, incredible. That is your perception of the world, your eye as a painter! You come from painting, and these overlays, grids, can be seen as an abstract painting. Mondrian would go nuts. There’s all kinds of different things. There’s kind of rigid patterns and there’s all kinds of abstractions. Everybody that would go in there… but the camera would take different things. Each person would take a different thing. I guess some wide shots are okay, but I am really more like “closer and closer,” and that’s where it really gets me going.

P: There is a tension between the wide shots and the views on details, on ordinary mundane things.

D: Exactly. They pull you to them.

David Lynch Untitled Lodz 2000

P: These photographs, are they going back to the late seventies, early eighties?

D: I can’t remember. It could have been in the eighties, but I don’t really know. It was after The Elephant Man. I always heard that the north of England had the greatest factories. That it was fire and smoke, and just pure beauty. So I organised a trip with Freddie Francis, the great Director of Photography of The Elephant Man and lots of films. Anyway, we drove from London north, and I don’t know, I probably missed it by just a few years. Everywhere we went the factories had all been torn down. There were just fields and the smokestacks were all being torn down. They were taking the smokestacks down. One after another. And the factories that they put up in place of the old factories were corrugated metal, little bitty things, zero personality, zero beauty, and it was a very depressing trip, very depressing. There was a couple of things we got but the big factories were gone.

David Lynch Untitled Lodz 2000

P: The process of decay is coming to an end in England and the industrial landscape is disappearing. How is it in Poland?

D: It’s going away. Everything is going away. One place I photographed in Poland, in Lodz, it was a great factory. Now they have the facade but it’s all sandblasted, so the bricks look kind of pink-orange and behind the pink-orange bricks is a super modern mall, a shopping mall. The mood is just completely gone. So these factories are disappearing before our eyes. It’s terrible. I mean it’s good in some ways, I guess; they were great polluters, really good polluters. But the fire and the smoke and the sounds and the life has a feeling that I personally love. And it’s a sadness to see it go, for those reasons. Just like in London there used to be fog, you know the London fog, and it was from burning peat or whatever, and it was very hard on people, but it had a mood. It had a mood. And a dreamy kind of mood. And now, London, you can see everything, and everything is modern. And when we finished The Elephant Man, within two years Freddy told me: “David, remember when we shot this and this and this. We couldn’t do it now. It is gone, gone.”

P: So your photographs are a witness to this.

D: Yes, I captured it. Yes, definitely.

P: And you are looking forward to continue capturing some more in this way?

D: Oh yes. I went to Poland on this last trip and I always asked them, because Poland has a lot of factories, but they moved to a different town. And this town was not an industrial town. But they had, in the woods, building after building after building after building where one-quarter of the munitions used in World War II were manufactured. And these buildings were hidden in the woods. And they were separated one from another in case one blew up. And all the buildings had trees on the roofs, so when planes flew over you couldn’t tell. But the Russians took the machines away after the war, so these are just empty buildings. And I thought: “Well, I’m not going to get anything out of this place.” But the more I looked, it was really beautiful. And there are still many, many little details left and many abstractions, so, yes, there are still places around. You know, it’s just a question of having the time and access to them. They’re still around.

David Lynch Untitled England late 1980s early 1990s

P: This atmosphere they have, you cannot substitute it for anything else.

D: No, there is no substitute for this. I like nude women and factories. So there’s always going to be nude women, I hope. And factories are disappearing.

The Photography of David Lynch: Interview