In Conversation: Paul Hackett

Originally from Glasgow, London-based Paul Hackett has worked as a photojournalist for more than 20 years. He has produced a staggering amount of incredible work during his 15-year stint, working as a freelance photographer for Reuters, the world’s largest multi-media news agency and 10 years for the Sunday Times. His work ranges from political subjects to white collar boxing and war zones

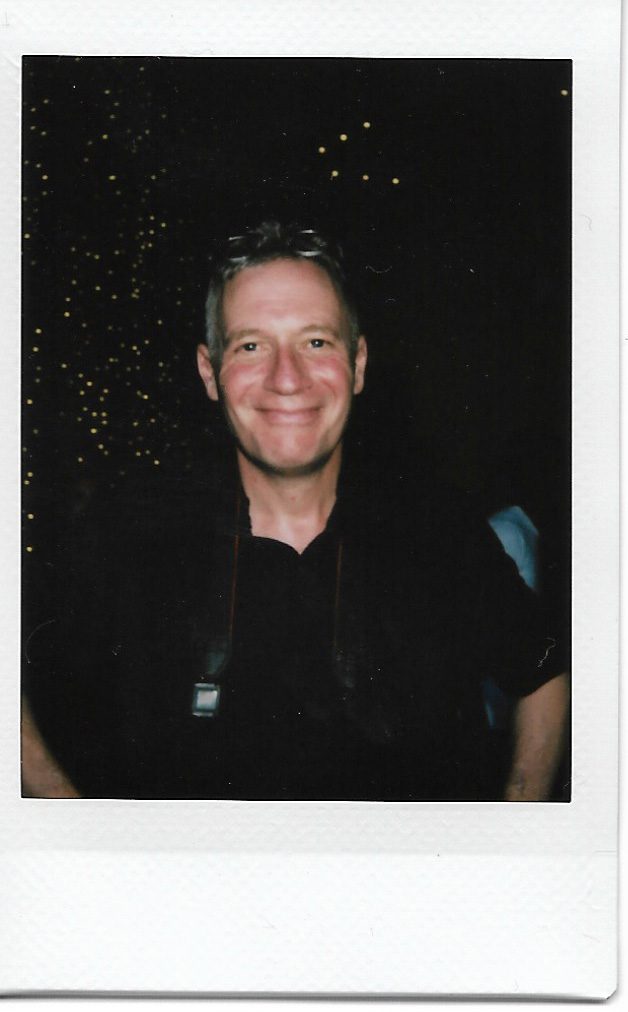

PhotoBite’s Simon Skinner met with Paul at a recent event in Brixton. The launch of a project for Reuters Wider Image platform, which records the trials and tribulations of being a Grime artist in London and forms a part of a European-wide initiative that strives to highlight the importance of photojournalism in telling the stories that need to be told.

Mairie McGillivray dances on the beach at Bridgend,on the Hebridean island of Islay (part of a series on young voters in the Scottish referendum), 2014.

You can read more about the exhibition and Paul’s incredible collection of resulting images HERE

Just ahead of the Slew Dem Crew hitting the stage at POP Brixton, Simon sat with Paul to talk about photojournalism:

Simon Skinner: Hi Paul, it’s great to meet you. You’ve been working professionally for more than 20 years, now. What was it that first drew you to photography as a medium?

Paul Hackett: Looking back to those, very early days when I first got interested in photography, I was encouraged by the kind of lifestyle that I could see came with the territory. No two days being the same, and being able to experience even the smallest part of history, really appealed to be at the start of it all.

SS: That suggests a journalistic approach from the outset. Have you ever pursued photography as a creative art form, or have you always leant more to a documentary style?

PH: I’m a news photographer and that’s where I feel most comfortable, but for me, it’s also where the power of photography lies and that’s what interests me. I’m just not that interested in the art-photography world. I believe that it’s one of those things that you can wrestle with, ultimately reaching a point, where you have to say, this is who I am. I’m interested in photojournalism and these are the things that excite me.

I still love looking at news pictures and I can go through the Reuters wire every day and be blown away with the stunning, important and powerful work that’s constantly being fed through that wire.

Stephen Lawrence murder suspects leave the MacPherson Inquiry, London, 1998.

SS: So what would you consider to be the greatest challenges for those working in photojournalism today?

PH: Well, it’s no secret that the editorial market is shrinking and it’s a topic of frequent and ongoing conversation. Frankly, it’s become harder to make a living in it.

SS: Do you think that’s down to the media landscape diversifying or do you think it has more to do with a greater number of people having the ability to shoot reportage photography to a sensible, publishable quality now, with the arrival of mass- market, high-end smart devices and endless opportunist, citizen photographers?

PH: I think you’re right to identify both of those things. Just imagine what it’s like now when a story happens. In most parts of the world, everyday people are now taking the sort of news pictures that a professional news photographer could have only dreamed of taking, [even just one of during their whole lifetime] a few short years ago. It’s happening all the time.

There were some amazing pictures taken recently, at the London Bridge incident that made you think, just how incredible the shots that these ‘citizen journalists’ are managing to capture. By the time the professional guys got there, they’re faced with shooting a taped off area that will ultimately demonstrate the same taped off area as the next guy, [and every TV station].

A man casts his vote as another registers at a polling station in the Kandahar, Afghanistan, 2004.

SS: Then, I guess there lies the difference between selling news pictures in a reactive manner or working with magazines [where possible] and agencies in the way that you do, to produce more project based material.

PH: Well, what I hear people say on the subject, and I think that they’re right, is that to survive and to move forward, there has to be the quality of the idea. I believe that’s just right, isn’t it? I mean, if you want to exist in this modern world of photojournalism, you’ve got to come up with good ideas, you’ve got to pursue them yourself, you’ve got to be able to work across multi-media; you’ve got to be able to do all of those things to be able to survive.

SS: True. The editorial work is, somehow, as important as the photography in many ways. At least in terms of career progression. How do you find the time to work on personal projects and how do they influence your commercial work?

A gazelle stands in the bombed out ruins of the compound of the head of the Libyan Intelligence Service Abdullah Al-Senussi in Tripoli, 2011.

PH: I’ve increasingly started to work on a number of projects, but in fairness, they’re not [all] strictly personal projects; I have been talking to [Reuters] Wider Image about them. I want to keep them journalistic-based and I don’t intend for them to go on for years. I want to know when they’re going to finish or I definitely run the risk of getting distracted and I know that I won’t see it through. So for me to develop that side of things, I’ve got to choose my projects wisely and there are one or two that I’m working on at the moment, which are kind of similar to each other. I plan to work on them over a few months and I’m getting more into the discipline of that, now.

SS: How would you describe your work ‘structure’ of late?

PH: Well, you have the projects we’ve just discussed, then I’ll have my daily commission work [via Reuters], and I have a few corporate clients, too, so I have to juggle my work around in the way that everybody does in order to survive.

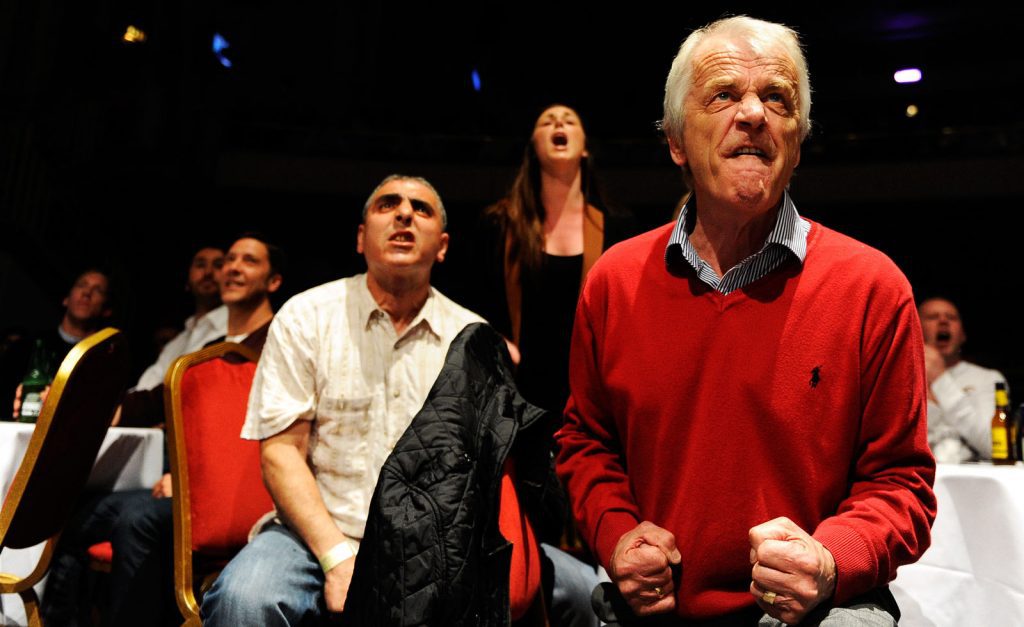

People cheer on a friend during a fight at a white collar boxing event on the east end of London, 2012.

SS: There’s just one more thing that I want to ask you at the moment, given our limited time before tonight’s show kicks off, and it’s a question that came up at the recent Byline Festival. PhotoBite hosted a panel discussion with Bernardo Conti, Jeremy Hunter, Giles Duley and I, on the nature of photojournalism and how it serves us in the era of ‘fake news’. Really, it all boiled down to the question of whether there is truth in photography. What’s your view?

PH: [Ponders] That’s a really interesting question. What did Giles say?

SS: He said that he didn’t believe that there’s truth in photography, but there can be a level of honesty.

PH: Interesting. He’s an interesting guy. Instinctively, I would say yes and I think that’s why I’m still interested in photography in the way that I am.

SS: Thanks for your time, Paul.

Paul Hackett