The Evolution of Audio with Julian Wallinger

Words by Julian Wallinger

Looking back, the audio technology we used all those years ago, was just what worked for us at the time. Then, it was cutting edge and definitely nothing to moan about; It’s only now, having been asked to think about it for PhotoBite, that it seems so restrictive and so different from how we work now.

Anybody working in TV knows that the ‘soundie’ loves a good moan [and a biscuit], and it seems I’m all out of biscuits, so shall we?

Fox’s Party Rings: The staple diet of the jobbing soundie.

When I joined Hammerhead TV Facilities, I was camera assisting. Coming from a skateboard and BMX filming background, the emphasis then was on making sure the action was captured, rather than the finesse of the shot. It took me a while to understand that, that transferred to being in the sound department rather than with the camera. Sound needs to be captured at a certain quality and the hook is in the difficult situations. Pictures are mostly a choice of moods or styles and take a lot of tinkering and need patience.

I was kicked out to freelance at the beginning of summer in 2002. 3 years is the norm when working in facilities houses, usually made up from a year running for them, a year learning how to use and maintain the gear, and a year on location earning them money.

I was eager to leave as soon as I could. I knew I was ready.

Being a sound recordist back then was a lot more standardised than it is now. The beautiful, hardy, analogue 4 channel SQN mixer, Sennheiser MKH416 and Audio LTD 2020 radio mics were what most productions took for granted and would turn up to a job with. Documentaries were made within these parameters mostly.

The only real addition would be a DAT recorder to double the weight of kit you had to carry if you were shooting on film. Oh, and a clapperboard of course.

Old faithful

It felt unusual to record independently for these occasions, because most jobs [being video], are only mixing and with the sound guy being tethered to the camera [and with picture and sound being recorded together]. The sound equipment was just an extension of the camera.

Mexico 09-10

This also meant that you were just ‘helping’ out the camera person, essentially. You’d spot for them if you were doing observational stuff, keeping an eye out for the next shot. This meant that some of them would just see you as a camera assistant and would give you instructions as to where they wanted lighting stands and things. I’ll help out on my own terms, cheers; I’m not gonna answer their call again [etc]. Needless to say, you had to be good mates with the camera operators, especially as it would ordinarily be them who would be getting you onto jobs in the first place. But that was part of it, productions would get in touch, firstly with cameras, and then they’d bring on the sound. That would usually mean calling up the soundie that they got on with or had used regularly. A brief phone call and meeting and you’d find yourself at an airport, whilst camera ops were called into production meetings and go on reccies. The amount of times I’ve got to a location and seen peoples faces when it dawns on them they didn’t give a second thought about sound when out on reconnaissance. No consideration given to noise pollution, coming from airplanes, roadworks, school yards, heavy traffic… just make it work, please!

A good example of this would be when I worked on the first series of ‘The Apprentice’. So the standard set up consisted of a boom and three radio mic receivers. At the beginning of the series, I think that there were fourteen contestants, Sir Alan, his two sidekicks and maybe the odd punter here and there. Absolute and complete absence of any plan as to where you might end up by the end of the day though?

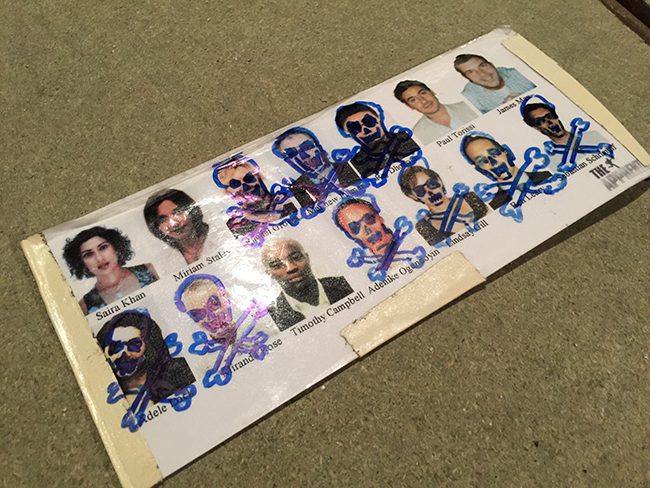

The crew ‘Hitlist’ from The Apprentice

Potentially, any combination of characters could be in a scene at any given time and it was always a fast moving day. I’d make sure that everyone was radio mic’d at the beginning of the day to save time, but it was a nightmare to quickly learn contestants names and radio mic frequencies so that I could quickly dial them in if they walked into shot!

With all contestants and crews in the same place, and with all the soundies gesturing to each other in silence about who they had, or shooting a ‘big wide’ with the cameraman telling me who’s entering or leaving the picture. This was about as close to a big studio set up as you could get for working out-and-about. Quite drastic work by today’s standards.

Tough guy or Chicken

Another situation I ended up in was working on a show called ‘Tough guy or Chicken’. This show was like a physical version of the apprentice and saw me travelling all over the world with contestants who had to compete against each other in local hardy tasks. There was a particular episode that stays in my mind, which was set in the Cinote caves of the Yucatan in Mexico, Amazing right?

The majority of the filming would take place above ground, but we would eventually have to venture into these caves and into the jungle, so we needed to think about how to cover the job. We were sent a couple of dodgy homemade videos of these caves [ahead of the shoot], which you could hardly make out as the video was so bad in low light, back then. We were told that there would be points where we would be up to our waists in water, but also that it was unlikely that we’d be filming at those parts.

“Our guide noticed that I was getting sunstroke and kept pouring water over my head to keep me conscious throughout the journey”

We had our standard kit to use top-side and we’d brought a smaller camera and some helmet cams along with a mini-disk recorder so that I could record separately, but keeping kit lightweight at the same time. All set.

When we arrived, we shot everything above ground absolutely fine and then onto the cave task. We packed down the gear and were given wetsuits. We started trekking through the jungle in the heat with the kit in the wetsuits, filming as we went, too. Our guide noticed that I was getting sunstroke and kept pouring water over my head to keep me conscious throughout the journey.

When we arrived at the caves, we then had to go down a rickety old ladder and into a hole, where the task was to start proper.

There were five guys being filmed, trying to complete this amazing underwater network of caves and to come out the other side.

Before I knew it, I was pushing a float along with my mixer, receivers and minidisk in a wetbag on top, whilst having to mix and swim at the same time. On and off for the first couple of hours!

During this time the cameraman could perch at certain points, to get shots, but I would have to stay within a certain range for the radio mics to pick up and some of these chambers opened up to reveal spaces the size of tennis courts.

Changing batteries in a bag whilst treading water is not easy. The thing with these kinds of programmes is that, when you watch it at home, the TV doesn’t really convey the reality that, whatever the guys on camera are doing, the crew has to do as well. And more.

If the guys are competing with each other, then the crew have to compete too, to get ahead. Set a shot up, film, pack up again and fight to get ahead to get the next shot.

Whilst I had condoms for the radio mic packs, to keep them waterproof, they were strapped to the contestants helmets because we were only going waist deep, right? Only at the last minute did I think to do something with the mic capsules. I taped little funnels round them to create an air bubble and to keep them dry as the mics were pointing downwards. Kinda like a diving bell. We carried on moving into proper potholing territory and of course, we ended up at a pass, where the guide pointed underwater and said” “There is a tunnel down here, which is waist deep and about eight feet long, after which you’ll pop out the other side”.

Waist deep, my arse! The guide went through, followed by crew who’s job it was to scramble through and to set up ready for the contestants coming next.

In hindsight, I wouldn’t have been up for doing that at all; but when you’re working with sunstroke, it’s too easy to go with the flow. I was amazed that the sound kit all worked when we finally came out into the forest. The helmet cams, which had to be connected to mini-DV recorders, were sitting in rucksacks full of water. No more recorders and ruined footage. Ah, those were the days.

Flash cards changed everything, but not quickly. I remember there was uneasiness around using memory cards in cameras with tales of lost footage, erased and recovered, which seems crazy now.

“Alasdair Mclellan was doing a shoot for Longchamp with Kate Moss. He was aware of the buzz of the 5DII and he was interested in seeing what he could do with them”

Sound Devices then also brought out audio recording devices with timecode. Huzzah! The 5DII came along too and shook everything up. For filming, the 5DII was relatively discreet and could be added-to in a rig, but it didn’t want added audio stuck on getting in the precious camera ops way. It was accepted that audio could be completely separate from camera.

It was around this time that, all of a sudden, there was a buzz that photographers could now shoot decent quality video. Around that time, I got a phone call to work on a fashion shoot, which was to take place in Morocco. Alasdair Mclellan was doing a shoot for Longchamp with Kate Moss. He was aware of the buzz of the 5DII and he was interested in seeing what he could do with them.

It was my first experience of being on a photography shoot as opposed to a video shoot, which was quite funny because they had booked a DoP and had flown him in from New York, me from London and then all the photography people to boot.

I got the call sheet through, which said to arrive in Morocco at breakfast time, around 8… this and that. So at 8 o’clock I turned up for breakfast and the DoP was there too. We were just eating on our own, thinking, where is everyone? The call sheet said that shooting starts at 10, so we found ourselves waiting around when eventually people started to turn up at midday with Gin and Tonics. I was wondering what the hell was going on and then quickly reminded myself that it was a photography shoot!

“I could handle this”, I remember saying to myself, but boy do those stills camera assistants get run into the ground. Anyway, I hung around for four days, waiting to shoot with the gear all primed before I went home after doing nothing. What a fantastic shoot.

But even then, production people wanted the sound to be recorded on the camera. I remember working on the TV programme, Cowboy Builders, and for the days where we’d confront the [dodgy] builders, they wanted the camera crew to not be attached to each other, so that we could all run in different directions if it all went tits up.

This meant that we now had a radio link between the soundie and the camera op. The camera was heavier and the camera op was now wearing headphones to monitor if the sound was reaching them. The time-code was synced but tradition was getting in the way. Slowly we got used to the idea that time-code was reliable for syncing in the edit and you only needed audio on camera for playback. Top mics like the Sennheiser MK440 shotgun all the way, I say.

The Sennheiser MK440 Shotgun Microphone

We were going through so much hassle to save about 5 minutes work on the edit and you’d find yourself explaining that you could do it cheaper [to production], but they wouldn’t have it. As more incognito and ‘sports’ cameras started to arrive on the market, the hidden camera shows naturally took off again.

Working with Sugarland TV who were at the forefront of the hidden camera rebirth we had no choice but to become inventive with our methods. Working on these programmes, you were never be able to predict how each hit would go, and you can’t just stop in the middle of your shoot to adjust equipment.

When shooting hidden camera/prank shows, finding places to hide microphones and then just adding more and more recorders and mics, to make sure certain situations were covered is now the norm. You’ve seen that guy just standing about in rain in the middle of the town centre, clutching a big heavy sports bag in an uncomfortable way, listening to his iPod and moving in odd patterns. Well, that was me, working.

We still had the range of the radio mics leashing us to the action, sometimes having to be hidden in shot.

The arrival of the iPad and GoPro ‘action’ cameras showed a growing gap in the evolution of consumer devices, and the speed that they were and are evolving is still staggering; whereas the rugged broadcast equipment of old, was just stagnating.

Whilst GoPros were adopted into the standard broadcast kit list, the idea that iPads could not be implemented, or tablets and phones, in general, could not be used as monitors, seemed archaic to me.

It was a funny period but eventually, things did start to change and ‘go digital’ in a sense. I think there are a lot more, smaller companies, now making peripheral broadcast equipment, compared to a few years ago; and more in line with consumer prices too. Timecode systems used to be thousands of pounds but now, a few hundred quid will set you up. Cameras are cheaper, even at the top end, and the most significant change in audio is that you can now record at the source.

Radio mics with internal recording capabilities; boom mics with internal recording, all time-coded; they’re all a fact of a soundman’s life now. Devices like Olympus’s LS Pocket series; especially the P1 have made the capture of excellent quality audio, supremely portable and the devices are tiny and unobtrusive.

Olympus’s tiny LS Pocket series

All these digital devices are now essentially computers with occasional firmware updates improving them all the time. It brought manufactures closer to the users in a day-to-day dialogue about situations. You couldn’t call yourself a soundie if you didn’t have a “Yeah I told Sound Devices I needed this or that” when the latest firmware came out with said fix on it.

I’ve never wanted to not be an Editor more! It has to be a nightmare, just getting bags of micro SD cards to sift through, as we harvest the action with so many intertwining stories happening at the same time.

It’s so nice to get a call to do a standard interview these days, when so many jobs are to sound harvest; even a fairly big drama is a far simpler job once all the preparation is done. The great thing about this job is that the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence. Once you are bored of the ‘system’ of drama, then you can chase a story in a documentary until that takes its toll physically, and you long to sit in one place again.

You never know who is going to call next.

Julian with The Hoff!