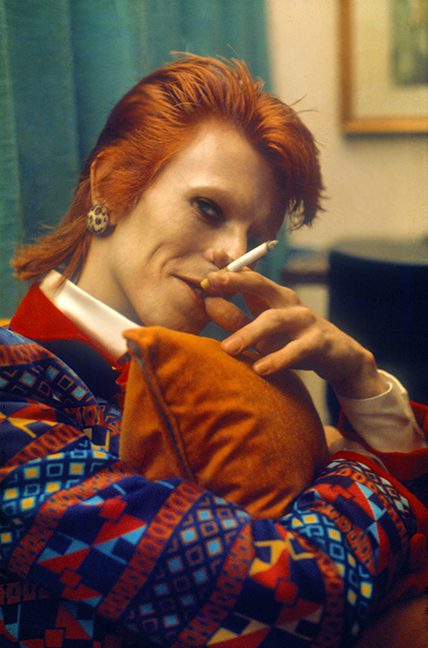

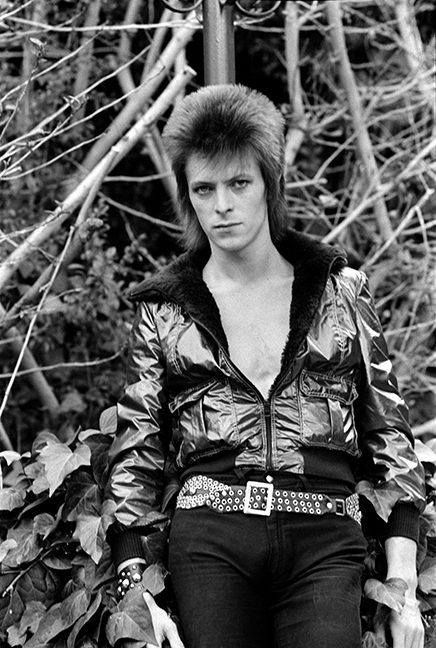

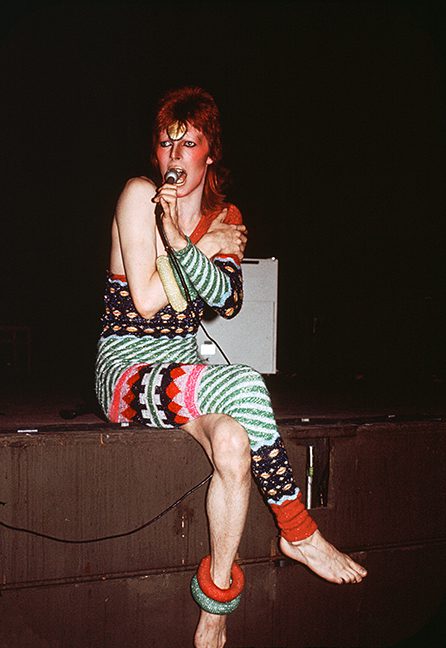

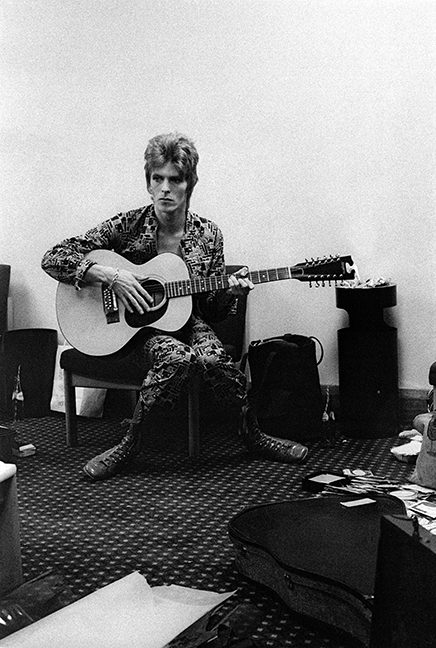

In Conversation: Mick Rock

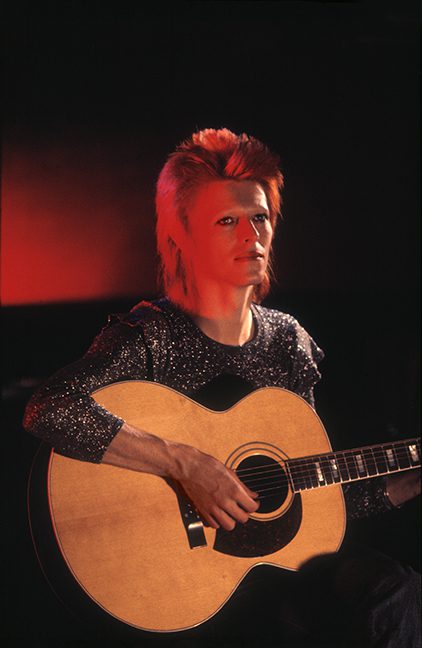

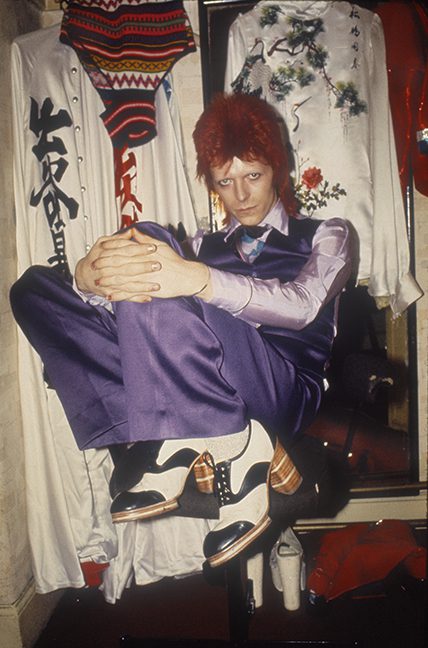

It was in 1972 when David Bowie released The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars; a seminal work, which challenged many preconceptions of what a pop star should be, who they should appeal to and introduced the world to Bowie’s, then alter ego, Ziggy Stardust.

Joining him for the ride was Mick Rock, a fellow Londoner, photographer and friend. Mick bonded with Bowie both creatively and personally, working as Bowie’s official photographer between 1972–1973.

Shortly before Bowie’s untimely passing in Jan 16′, PhotoBite’s Simon Skinner met with Mick in London to discuss very special collection of images from this period, to talk about his past; his time with Bowie, along with a host of other subjects from his prolific career as a rock photographer

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

Simon Skinner: Hi Mick So, where do you spend most of your time presently? You’re based in New York, right?

Mick Rock: Oh, I’ve been in New York for 30 years now.

SS: You still have a very British accent; and haven’t caught the US twang at all?

MR: No, I’m still a through and through Brit, even for someone who’s been living in New York for 30 years. I’m not going to lose my bloody accent. Fuck ‘em. They’ll have to put up with it.

SS: So Mick, you’re still out shooting; still doing your thing and taking commissions?

MR: Yup. I Never really stopped. I work a lot and I’ve been spoiled in New York over the years.

SS: Where are the best venues in NYC now? In another life, I was involved with a band and I played there a few times. I imagine, as with most major cities, the best spots change and move quite regularly?

MR: Where did you play?

SS: Well, a number of places, but the highlight was a date at the Bowery Ballroom with The D4 and Electric Six, [way back when].

MR: Oh cool. Yeah, well, that’s a good place. But that must have been within the last decade, right?

SS: Not quite, it was around 2003. So a little further back.

MR: Yeah, because I think the Bowery only opened around then, in fact.

SS: It was a fantastic venue. Really, really incredible to play, with a fantastic sound and a great team.

MR: So, what happened to you? It’s rough being in a band, right? I mean, to make money.

SS: We’re deviating from the point of this interview but yeah, it is, really. Things are different now, I mean, not necessarily easier but a different landscape. Think back to that time: Apple were making bold moves and iTunes was launching. The traditional companies, as they were, were very nervous. So, big deals weren’t being handed out readily. And whilst we had a decent publishing deal in place with Warner Chappell, we struggled to land a decent album deal and it just became very tough to keep the wheels turning. We did a lot of touring with bands like the Libertines and a few other bands that broke through in the early 2000s, though.

MR: Cool.

“I’d spent a disproportionate amount of time in my youth, studying the pages in the NME and always found the pictures at least as powerful as the words on the page” Simon Skinner

SS: It was great fun. We toured with the Libertines, pretty much for the whole first album tour. Not long after James Endeacott signed them to Rough Trade Records. We wrote and recorded a fair bit, and worked with some decent producers, but never got a full album together in the way that we wanted to do it. I’ve always been making pictures, though. Firstly in graphic and illustrative form, swiftly followed by photography and film. It’s me that has the image archive from those tours. I had spent a disproportionate amount of time in my youth, studying pages in the NME and always found the pictures at least as powerful as the words on the page. The journalists could be as ridiculous as they liked, [and often were] but the pictures told the whole story. It’s here that I first came across your work. Anyway, we eventually disbanded and I got into publishing. There you go, there’s my story.

MR: Oh cool. It’s a bit more of a sedate profession but, nevertheless, it’s a little bit more solid. The book trade’s a bit up-and-down, I know.

SS: Yeah, it is I guess. It has its moments, though. I have the opportunity to talk to people about their creative endeavours, which is a real privilege. People like you, Mick.

“I always like people to get a bit excited about my work. They don’t have to be excited about me, so long as they’re excited about the work” Mick Rock

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

MR: Well, it’s very nice to hear that. I always like people to get a bit excited about my work. They don’t have to be excited about me, so long as they’re excited about the work.

SS: It’s an impressive archive, Mick, There’s no denying that fact, and it’s all there for everyone to see, isn’t it? Plus, the [Taschen] book is an incredible snapshot of your time with David Bowie, whilst your book, Mick Rock: Exposed, which came out via Palazzo in late 2014, was more of a career overview [so far]. Was the Palazzo book a reissue or first edition?

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

MR: It’s not technically a reissue; it is the softback version of a hardback that came out in 2010. Different cover; the original cover was a shot of Bowie from 2002. It was a kind of darker looking shot with his scarf covering his jaw and that. But I decided on this one that if we’re going to put it out again, let’s make it a bit different. I like the format too. It’s better, in a certain sense, for galleries. I mean, at galleries and events, people want books. It’s much easier to trundle these around than it is the [larger] original. But I like it. I like the size, I like the feel of it. I mean, it’s a quality piece in terms of production, so I’m happy about it even though, actually, the content is the same as the 2002 hardback. But the 2002 hardback is discontinued, so this has moved in to take over, as it were. The size thing seems to be something of a trend in the industry, to produce these smaller versions. It may be. I don’t know. But I like them; they’re cheaper, they’re more accessible and they’re easier to move around.

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

SS: Maybe you can tell me a bit about some of the work you’ve been doing lately, Mick?

MR: Well, I recently had a big exhibition in New York, which enjoyed lots of media attention. I also shot Lenny Kravitz a short time ago for a magazine called Flat; for the cover. I also shot Iggy Pop for this company called Sailor Jerry, and, of course that was fun because Iggy is an old friend of mine, dating back to the Raw Power days. The amazing Iggy is, of course, still going.

SS: He keeps busy, doesn’t he? He’s been recording and presenting a show for BBC6 Music, hasn’t he? I think he’s been doing it from home and just broadcasting it. But I listened to a few of those. They’re bloody good, actually.

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

MR: He’s very bright. He’s much brighter, I think than people originally thought. They just thought he was a lunatic in the early days, but he’s actually very bright and very well-read, and heavily into art; he’s especially into ancient art… It’s a very eccentric place: tucked away, and a little bit like a place where Gauguin would have stayed in the Pacific when he ran off and started producing his masterpieces. And, of course, he actually does his own paintings. Very punky paintings indeed!

SS: It’s been enlightening, to me, to listen to his radio show; just how generous and transparent he was about a lot of things, and how honest he has been.

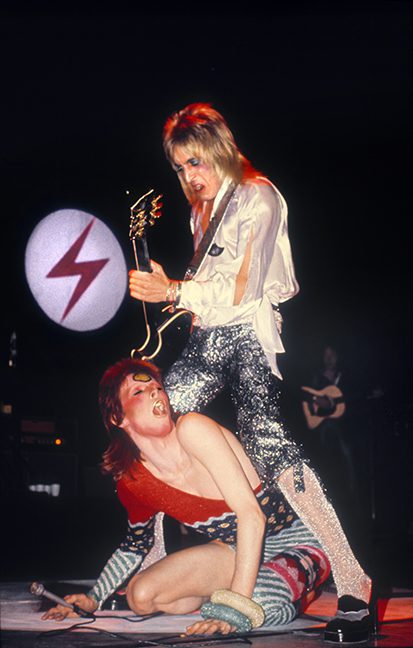

“Iggy can’t do the backbend anymore, you know, like my famous backbend shot, which is about as rock ‘n’ roll as you’re ever going to get” Mick Rock

MR: He is a very honest person. He’s extremely honest. There’s never anything fake about Iggy in fact. Well, the amazing thing is that he’s still going, with all that energy he’s put out and all that jumping into crowds. And he said he can’t do the backbend anymore, you know, like my famous backbend shot, which is about as rock ‘n’ roll as you’re ever going to get.

SS: It’s impressive, and of course, that picture features in the book, Exposed.

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

MR: Oh yeah, that goes everywhere with me. That never leaves my side. And things like Transformer. That past never goes away. I mean, that’s what amazes me: how this stuff just sticks around, you know?

SS: Well, the images become iconic, don’t they? A while back, I interviewed Gered Mankowitz – who I believe you know?

MR: Yeah, I know him. Oh well, he’s got the best studio shots of Jimmy because… Listen, we all get lucky. He happened to be wearing that uniform that day, you know? Which he only wore on certain occasions, but it was like the guy that did the Kurt Cobain pictures when he’s got the hat and the big goggles on.

SS: Jesse Frohman’s, The last session?

MR: Yeah. I’m sure he’s done some other good stuff, but I’m not aware of anything else he did. But those [pictures] have become his, and it happens quite a lot. Of course, Gered has a much bigger archive than most.

SS: Well, he’s got plenty of it, hasn’t he? 50 years to draw upon.

MR: Yeah, I don’t think he’s shot much in recent years; I think he’s decided he’s had enough of the shooting and just got stuck in to marketing those Hendrix pictures alone. I’m sure they make him a bundle of money.

SS: I’m sure they do. He does a bit of lecturing and lives on the South West Coast in the UK. He’s been known to run the odd classroom at Falmouth University. One thing I asked him during our conversation was about his subjects being his calling card, and you’ve sort of partly answered it, really. I mean, what I asked him was, did he think that he had earned his stripes and gained his name, if you like, through the ultimate fame of his subjects?

MR: It was the Stones that put him on the map, actually, I think it was Marianne Faithfull, and through Marianne, he met a guy called Andrew Loog Oldham, who became a friend of mine in the late 70s. He was the original boy wonder Manager and producer of the Rolling Stones. Gered then went on to shoot those Rolling Stones pictures and then, from there, the Hendrix stuff. And, of course, he’s shot a lot of other stuff.

SS: Absolutely. Looking through his most recent photo book, it’s an incredible body of work there. You know, 50 years is pretty much the rock ‘n’ roll history book, I guess.

“I sprung in late ’69 with the Syd Barrett pictures. I actually did a couple of Rory Gallagher album covers, and then David Bowie and I crossed paths. Then, of course, Iggy, Lou Reed, Roxy Music, Queen and Rocky Horror” Mick Rock

MR: I would say so, yes. He was out of the paddock a little bit before me; a few years before me, in fact. But I sprung in late ’69 I suppose, with the Syd Barrett pictures. The Madcap pictures of him. Of course, I actually did a couple of Rory Gallagher album covers, and then David Bowie and I crossed paths. That was definitely significant and then, of course, Iggy, Lou Reed, Roxy Music and then Queen and Rocky Horror. So, it was an interesting period of time for a young lad who barely knew what the hell he was up to.

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

SS: Absolutely. So, did you have any official photographic training or did you just pick a camera up and try it?

MR: No, I was studying modern languages and literature at Cambridge in the late ‘60s and I actually picked up a friend’s camera whilst on an acid trip. I was very, very high. You didn’t really know the strength of what you were taking back then. It was like blotting paper acid, where you never knew how much you were taking.

SS: The real deal, huh?

MR: Yeah, some of us were so high we couldn’t take any more at times. So, anyway, there wasn’t actually any film in this camera but the excitement I got from it was like nothing else. I remember every time I would hit the shutter, it would click and felt to me like a big explosion every time. Somehow that all got into my psyche and I started to play. I then actually borrowed my friend’s camera on another acid trip and got some pictures that I’ve still got somewhere, buried deep in my archive, and it kind of trundled on. Then some local band; I can’t even remember their name, though I’ve probably got it on a set of negs somewhere; they offered me five quid and I thought, ‘You mean you can make money from this?’ and, you know, my parents didn’t have any money, I was just… Well, it didn’t matter back in those days. You really didn’t need a lot of money. It’s not like today, you know? And then, from an old mate, I got a Pentax camera for cheap, I bought a cheap lens for it; a cheap wide-angle, and that’s when I shot my mate, Syd Barrett. That was very important, in many ways, partly because he was my mate, partly because I’d taken an acid trip with him maybe about a week before the session, and partly because of Syd being an extraordinary subject. Yes, there are a few pictures outside of mine; there were obviously some when he was filming Pink Floyd, but I’ve got the biggest collection of post-Floyd Syd pictures that have somehow become fairly definitive. And it just kept rolling along, almost on it’s own, when I wasn’t really thinking about it; I was thinking maybe I’d be a writer, maybe I’d make films. I mean, photography wasn’t so highly regarded in those days, but I enjoyed it, I enjoyed the fact that it was so non-cerebral, non-intellectual, purely instinctive. And yeah, you had to know a little bit about it, but you didn’t have to know that much to get away with it. I mean, I know Gered didn’t get any formal training either.

SS: That’s right. He worked for a newspaper. His father bought him his first camera.

MR: Yeah, Wolf Mankowitz, who, in his day, was very famous, although he’s dropped into obscurity for most modern people. But in his day, when I was a kid, I remember him, especially the name, you remember a name like his don’t you: Wolf? It’s a great first name. And it just kept rolling. I mean, you couldn’t make a lot of money back then, but it didn’t really matter. I remember I was doing lots of things. I’d write little pieces, take pictures. I actually did a little bit of modeling, like a hippie model. The first time I met Gered, he shot me for some book cover; I think maybe me and a girl, and he was already successful. Me, I was just scratching along. Anyway, I never had an agent, certainly, I never had an assistant in those early days. But I had a personal assistant by 1973 and that would probably be post-Ziggy, that’s when she locked in. And it was then that it kind of moved in and took over, while I was thinking about other things; I wasn’t really obsessed, per se, with photography, but I became obsessed with the images, the access it gave me to imagery. And, of course, I was very buzzed about these characters, whom I really saw in the same vein as the some of the lunatic poets, especially the poets like the French Symbolists or the Beat poets or the English Romantics, you know? So they got in my mind because that was my education, and that’s how I saw these early characters that I shot. And now people call it a career and I go, ‘I suppose it has been a career’. That wasn’t the way I thought about it. You couldn’t go into it thinking, ‘Oh, I’m going to be a rock photographer. Okay, you’re going to be a rock photographer. You’ve probably got about two years and then you’ll have to get a real job’.

SS: Sure. But like you say, it wasn’t held in such high regard at that time. And Gered said the same, actually. Going back even further, Steve Schapiro explained to me how, in New York, there were very few galleries exhibiting photography as art.

Andy Warhol once said to me: “I like photography much better than art, Mick. It’s so simple.” I thought that’s great. He loved it because of its simplicity” Mick Rock

MR: Nobody regarded photography as art. Maybe with rare exceptions; somebody like Man Ray had garnered something of that image. I think Andy [Warhol] had a lot to do with it. I think Andy helped photography because his art was so heavily photographically based. So, I have a theory that Warhol did a lot for photography, albeit that he mostly stole other people’s pictures. But then, after a while, he started to take his own pictures. In fact, he once said to me: “Oh, I like photography much better than art, Mick. It’s so simple.” I thought, that’s great. He loved it because of it’s simplicity.

SS: But then that was largely the basis of his work. The fact that it was demonstrating the simplicity of creativity and art, and it didn’t need to be complex or clever to demonstrate beauty.

MR: Right, it didn’t have to be Salvador Dali. Although, he was a big hero of Andy’s because, I think although they were radically different characters, he liked his self-promotion. Salvador Dali was an incredible PR man. You see films of him talking and he was an incredible self-promoter. But he sort of did it in kind of an anti-self-promotion way, you know?

SS: It was a kind of covert, wasn’t it?

MR: You know, he used to lie about things. He’d say something like: “Oh, I don’t really have much to do with my art. I let other people get on with it.” But I’ve seen tonnes of images of him pulling his silk screens. So, he really did have a lot to do with it. He had his hands all over it but he pretended he didn’t. It was this perverse thing that he would do.

SS: Well, he was a terribly aloof character and I guess that’s indicative of that behaviour, really, isn’t it?

MR: Yeah, it is. But it works. I mean, I don’t know that it would have worked for anybody else, but it worked totally for Andy. And he invented, as it was, postmodern art. He was more than just a Pop Artist; just look at the price of his work in auction nowadays. I know people that got stuff off him in the late 60s and 70s, sometimes to pay off a debt, sometimes a friend for a few hundred dollars, they became millionaires as a result of hanging on to their pieces. Pieces like the Marilyn one, which is so famous, I think it’s the red Marilyn. But he made a lot of those including a lot of smaller ones. And even though they’re not all worth $50 million, you know, they’re all worth at least $1 million.

SS: We’ve spoken more about me and about Andy Warhol than we have done about you. You explained how you got into image making, but the question I also put to Gered was about the nature of the work. I mean, obviously, with the lifestyle choice as well, for you, I guess being involved in that world is very exciting.

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

MR: Uh huh. I felt at home. I mean, remember, these were the days when there was something called ‘the underground’ and also the thing of being on the outside, like a rebel. I mean, I said to a mate of mine the other day, ‘What the fuck happened?’ And we’re in museums, we’re in art galleries, we’re in cultural centres all over the world, which is so kind and respectable, and that was the last thing we were looking for or thinking about. I mean, it was all supposed to be edgy. Look at the characters I hung with. Those core three of David, Lou and Iggy. People talk about trying to shock today but back in those days it was so real. Like the Pistols, when they came along a bit later, they upset a lot of people. They put people through psychological changes: just the idea of them and the subjects that they were dabbling around in. It’s impossible today because everything’s out of the bag; there are no secrets. You weren’t really getting a huge amount of insight into the characters themselves. Anyway, the other question people go on at me about, of course, is film and digital. I go, ‘Fuck it, I love it.’ I love shooting digitally. But what I do like is the fact that, as, of course, in Gerard’s case, is that the work of mine that’s worth a lot of money that people have offered me, well, certainly well over £1 million and more for certain collections of mine, like my Ziggy Stardust collection, alone, is over 5,000, maybe 6,000, images and I have a load of footage as well. So, it’s a strange but fascinating world. But you have a true master. You have the black and white negative or you have the Kodachrome. And those are objects, you know? They’re things that you can actually physically touch, whereas with digital, it’s all on computers. So, it’s a whole different ball game. But ultimately, all I care about is the images. I’m not really a purist in any way. I don’t have a lot of cameras, I never did. Most of that early work was shot on two cameras; a Nikon and a Hasselblad and my Hasselblad was always a wind-on camera. The CM and the Nikon were both out of the late 60s. By the time I got them second hand, they’d been around for a little bit, and they served me well. Later on, I maybe had to replace them both but I replaced them both with the same camera. That was it. I worked with the two cameras and nothing else. And, obviously, now I have a couple of digital cameras.

SS: What are you using now?

MR: Well, I use Canon a lot. Nikon also have great cameras, one of which I actually did an Internet campaign for that was buzzing around. So, that’s actually a fine, fine camera.

SS: Let’s talk about your Ziggy archive.

MR: I’m putting out a new book with David and Taschen, [remember, this interview is historic – Simon] and half of it’s going to be previously unseen material. So, that’s what’s going on with that.

SS: It’s great to know about the book but you suggested earlier that you have moving footage as well. How were you shooting that at the time?

“You know I did those videos? Of John, I’m only dancing, Gene Genie and Life on Mars! You may not have known that” Mick Rock

MR: Some of it was shot on a wind-up Bolex and some of it was shot on an Arriflex. Some of it I shot, some of it I got shot. It was actually with a camera assistant but he was the husband of a friend of my first wife, so, he did a bunch of stuff for me. And you know I did those videos? Of John, I’m only dancing, Gene Genie and Life on Mars! You may not have known that.

SS: I wasn’t aware of that Mick, no.

© PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

MR: Oh yeah, those are like, well, whatever people call them: ‘seminal’ videos. Although, obviously, the Beatles and the Stones and Dylan had done pieces before that. But check them out. And Life on Mars always gets incredible reactions. But I have a load of other footage too. Some of those are in the Bowie touring exhibition, and some of his wild footage is as well. I shot a bunch of black and white footage as well.

SS: I think we’re leading into part two of this conversation, Mick. Let’s pick up from here next time; it’s been great to chat with you.

MR: Likewise, and yes, let’s talk more next time. Thanks.

All pictures: © PHOTO COPYRIGHT MICK ROCK 1973, 2015

Mick Rock: The Rise of David Bowie

£450.00

Limited edition of 1,972 copies worldwide each hand signed by Mick Rock and David Bowie