Analogue vs Digital: A Photographer’s View

The argument over analogue vs digital photography is an argument that’s been since the advent of digital imaging and is now rather moot. With imaging technology development racing ahead at a seemingly exponential rate, questioning the quality of a digital photograph is no longer a matter for debate. The ever-increasing demands on the speed at which images are delivered to editorial houses or for social media means that digital is the only viable solution for most applications. Even though there are still labs that can develop your films in 30 minutes, they need to be digitised for delivery, so why go to all the extra time and expense to end up with digital file anyway?

For us music photographers in particular, digital cameras are both a blessing and a curse. ISO ratings of 3200 and [way] above, with relatively minimal noise or digital artefacts, mean that shooting in the terrible lighting we are subjected to, if we move away from the brightly lit arenas, is no longer the challenge it was. And shooting in RAW means that adjustments can be made to compensate for LED lighting colour casts, or convert to black and white when whoever is responsible decides that the band looks best under red lights.

The downside is that the concert photo pits are becoming massively overcrowded with people that have affordable, high-performance cameras, but that is a completely different discussion that is already done to death on forums and Facebook groups, and was touched upon in my previous piece here.

We have all heard the statistic about more photos are now being taken every hour/day/week/month than have been taken in total in all the preceding time since the invention of photography. The proliferation of digital photographic devices means that just about everyone has the ability to take photos at any time and, with the availability of cheap mass storage, in huge numbers, and usually with the lens pointing in the wrong direction.

The Rubens

There is no denying that digital imaging, whether still or moving, has brought about the so-called democratisation of ‘art’, although it is definitely a case of quantity over quality. And most of the pictures being snapped are ephemeral, especially on platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram. The reality is, every digital image is ephemeral, even those considered works of high art. By their very nature, digital photos do not exist. They are simply a massive collection of ones and zeroes stored on a piece of media that is at the mercy of electricity and/or the stability of said storage device. Who hasn’t suffered from hard-drive or memory card failure at least once, and invariably without an adequate back-up regimen?

This is where the argument over digital vs analogue takes of a more serious note, that goes beyond the hipster fad for all things analogue, or even how analogue sounds/looks better. The organic look of film does have a certain charm that you can’t get from a digital photo, no matter how many filters are applied to it.

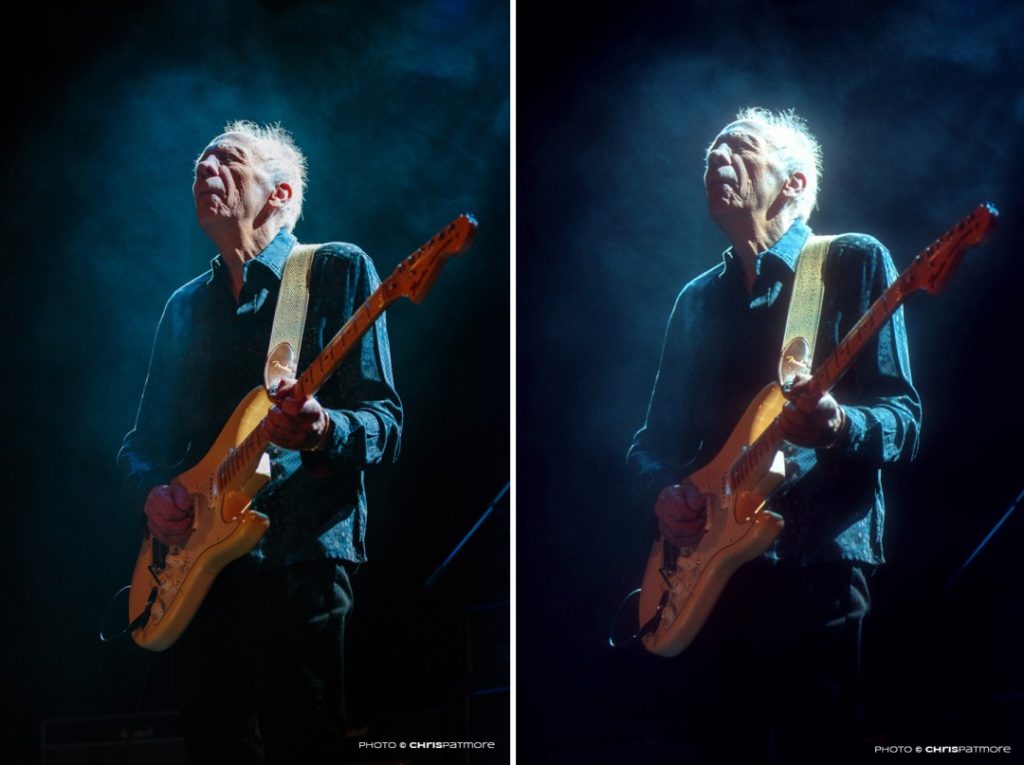

Robin Trower

I recently bought myself a Mamiya 645 medium format camera, with two lenses for around the same price as I paid for a used Fujifilm XE-1 with a prime lens. The Mamiya is a beast that is built to last. It’s technology being mostly mechanical is less likely to fail than that of the Fujifilm with all its digital circuitry. And without all the menus, the Mamiya is much easier to use, without having to rely on a manual, because everything is manual.

Apart from the fact that I always wanted a medium format camera since my early days as a photographer, but they were way out of my price range. Now they are insanely cheap to buy. The main reason I bought it was because I wanted to slow down sometimes when taking photos. Shooting live music is a rush. The lights are always changing, so you are constantly altering exposure [using autoexposure is asking for trouble], and there is non-stop action on the stage (and off). And if you are forced into the ‘first three songs’ situation, the rush/panic increases. So when a roll of film with 15 photos is going to cost more than a memory card that holds over 1100 RAW files, you want to take your time and make every shot count. Having grown up shooting film, I still apply that attitude when shooting on digital. I don’t understand the pray and spray methodology. I’d rather frame the shot and wait for the ‘decisive’ moment. Anyway, I digress slightly.

Clever Thing

As I was saying, digital photos do not exist. You can’t hold them in your hand and look at them without the aid of an electronic device. And with the short lifespan of digital and electronic devices, and the constant changes in media formats and their readers [who remembers SyQuest, Zip or Jaz drives, or floppy discs, or even CDs?], how long will our precious work be around? When I left Australia about 30 years ago, a box filled with hundreds of Kodachrome slides was left with my family, to be sent on later. For a variety of reasons, I lost track of its whereabouts. Last year an old friend contacted me out of the blue, enquiring about some of my old surfing shots that he wanted to for an exhibition. I asked my siblings if they knew where the box had ended up. My brother found them in his shed and posted them on to me. They arrived as pristine as the day I left them. I could hold them up to a window and see what I had shot almost 40 years ago. I have subsequently started scanning those practically grain-free Kodachromes [Paul Simon was right].

That got me thinking: I can digitise my analogue photos, so wouldn’t it be great to go back the other way and put my digital files onto film, to ensure they are still around in 30 years time. I know that Hollywood still archives its movies onto celluloid, even though just about everything nowadays is a totally digital workflow, from origination to distribution, they have not found a satisfactory archival format that is better than film.

So I did a quick Google search and came across a company called Digital Slides, based in Derby, that transfer digital files onto Fujichrome slide film [35mm, 120 and 5×4] or B&W negative. I initially ordered their free sample pack to check the quality, which was far better than I imagined. So as a test, I picked a few images from amongst my favourites, shot with my Canon 6D. The files were prepared on my old iMac, which hasn’t been colour calibrated, although being live music shots the colours are already exaggerated and far from natural.

The files were uploaded to their server late on a Wednesday night. The mounted slides arrived back Friday morning, using their standard service. Not a bad turnaround time. The results look stunning and matched what I saw on my screen, despite it not being calibrated.

With the slides in hand, the next part of my test was to digitise them using my Nikon Coolscan 4000 film scanner, which scans at up 4000dpi. As the slides are made from a digital file that is 4096 pixels wide, I opted to scan at 3000dpi so that the scan would be the same size as the digital file used to make the slide. Having not yet fully grasped the intricacies of the scanner software, a little post-scan colour correction was required to match the digital file. Some of the latitude of the original was lost in digital-analogue-digital conversion, but the results were satisfactory for everything except critical print work, and that was mostly due to the quality of the scanning not of the slide. In the sample images, the digital original is the first one.

So why archive to film instead of onto archival prints? Cost, storage space and future reproduction, although reproducing from a print is perfectly feasible. Whatever format you choose, archiving to an analogue medium is vital if we consider our images important or worthy enough to keep for posterity. How we originate the image is no longer an issue, whether digital or analogue, it is primarily a matter of using the right tool for the job. The real digital vs analogue debate now has to be directed at how we are going to preserve the images [and any sort of vital information] for future generations to be able to study our culture, and maybe get insights into how we lived, and, quite probably, where it all went wrong. If everything we have is archived on digital, then in the future, now could be seen as the second Dark Ages as there will no tangible record of our art and culture, beyond the tons of mysterious little shiny discs.